Data Management at the Energy-Water Nexus

By Lucas Stephens

As we work to create an internet of water – a world with more accessible, discoverable, and interoperable water data – we like to highlight the organizations who are contributing to this vision and explore the benefits they provide to water management and other sectors. The Groundwater Protection Council has been improving groundwater and energy data since 1983 and leverages that data to enable environmental protection and increased water availability. The resources they provide to state oil and gas agencies are essential to coordinating regional approaches in the energy-water nexus.

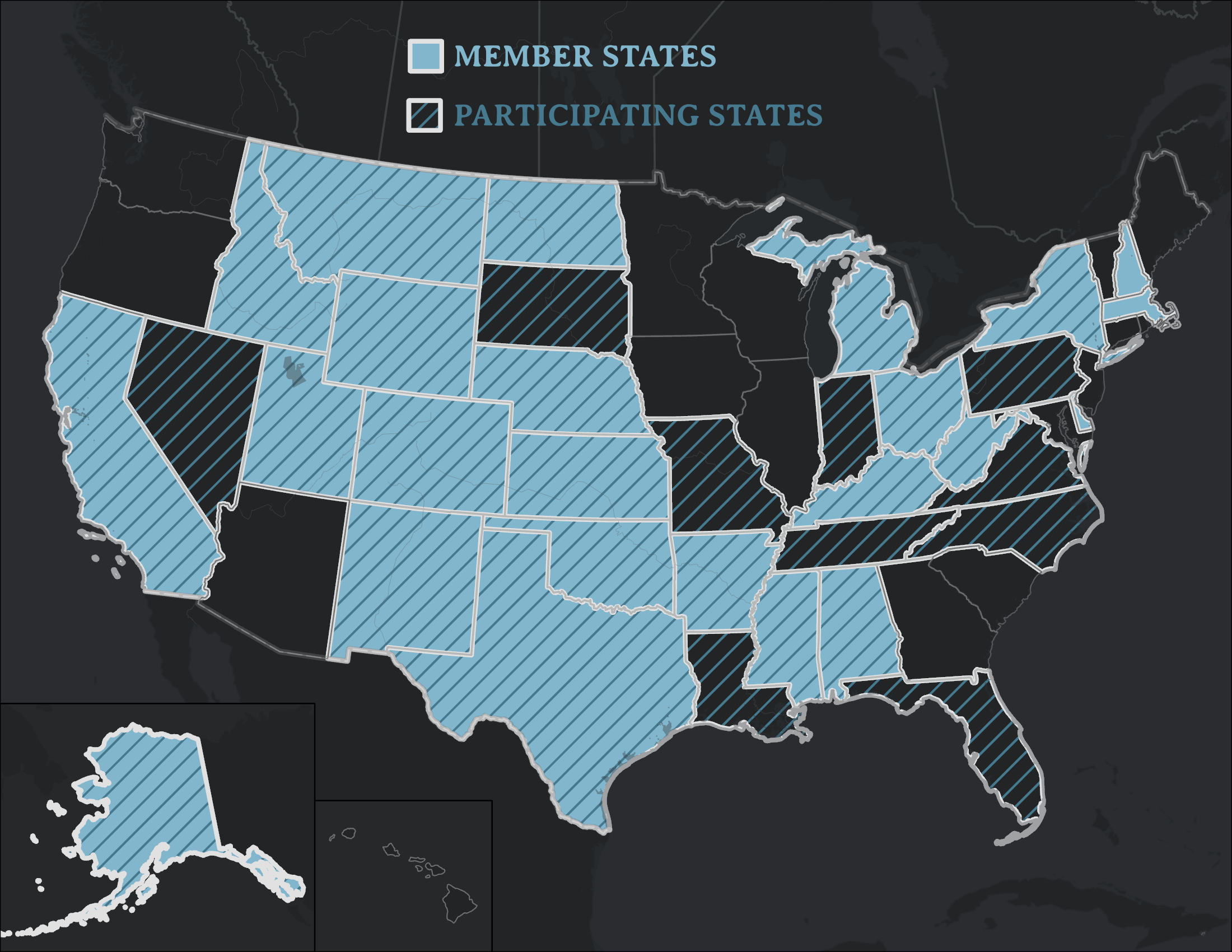

The Groundwater Protection Council (GWPC) is an organization devoted to the protection and conservation of groundwater resources throughout the United States. A handful of state groundwater regulatory agencies came together in 1983 to form the council, which has served as a forum for research and knowledge sharing ever since. Technical and regulatory experts who focus on connections between water (particularly its availability and quality) and energy production from oil and gas wells, inform new technology, regulatory standards, and best practices for the council’s twenty-four member states. Webinars, workshops, and trainings support the network, identify shared needs, and transmit new information among agencies.

In addition to the expertise that the council develops and disseminates, it also builds and offers a suite of integrated software to state agencies, under the umbrella of its Risk Based Data Management System. These programs primarily assist the regulation, oversight, and management of oil and gas facilities. Currently, more than thirty state agencies use at least one product to run a variety of services, including reporting data on underground injection control to the EPA, automating oil and gas facility data reporting, collecting field inspection data, online permitting, and energy production accounting, among many others.

Figure 1: Groundwater Protection Council Members and states participating in the Risk Based Data Management System.

Groundwater Data Management

The GWPC is an excellent example of states collaborating to leverage the water data that they collect independently, a common theme of the emerging Internet of Water. Exchanging data and information across state and jurisdictional boundaries can often be difficult, costly, and time-consuming. By providing data management software and setting common standards, the GWPC reduces those transaction costs, addressing many typical data challenges – and not just between similar agencies. Environmental protection, fish and wildlife, and public health agencies frequently need reliable information about oil and gas wells. Agency-to-agency data transfers, even within the same state can be burdensome and difficult to integrate without consistent services. GWPC provides the consistency needed to facilitate these data transfers. Energy industry operators and the public are also able to access water data through the GWPC, improving communication and transparency.

The technical assistance and data management that the GWPC provides agencies saves them time and money through automated workflows for data processing and analysis. These longstanding relationships exist somewhat outside of governmental structures but are often essential to smooth government coordination and operation.

Similar to many organizations that routinely aggregate data, the GWPC faces problems with accessibility and integration. With so many states contributing data, any update to a state’s system can throw a wrench into the automated, consistent collection and standardization of groundwater data. Uploads have to be timed carefully. Additionally, some data that the states collect is proprietary. Sorting through what details can be made public and accessible (the ultimate goal) can sometimes be tricky. Often the necessary data to track groundwater quality is split between individual agencies that regulate oil and gas production and agencies that regulate groundwater. Aligning standards and maintaining connections with all of them can be a challenge.

The Well Finder App

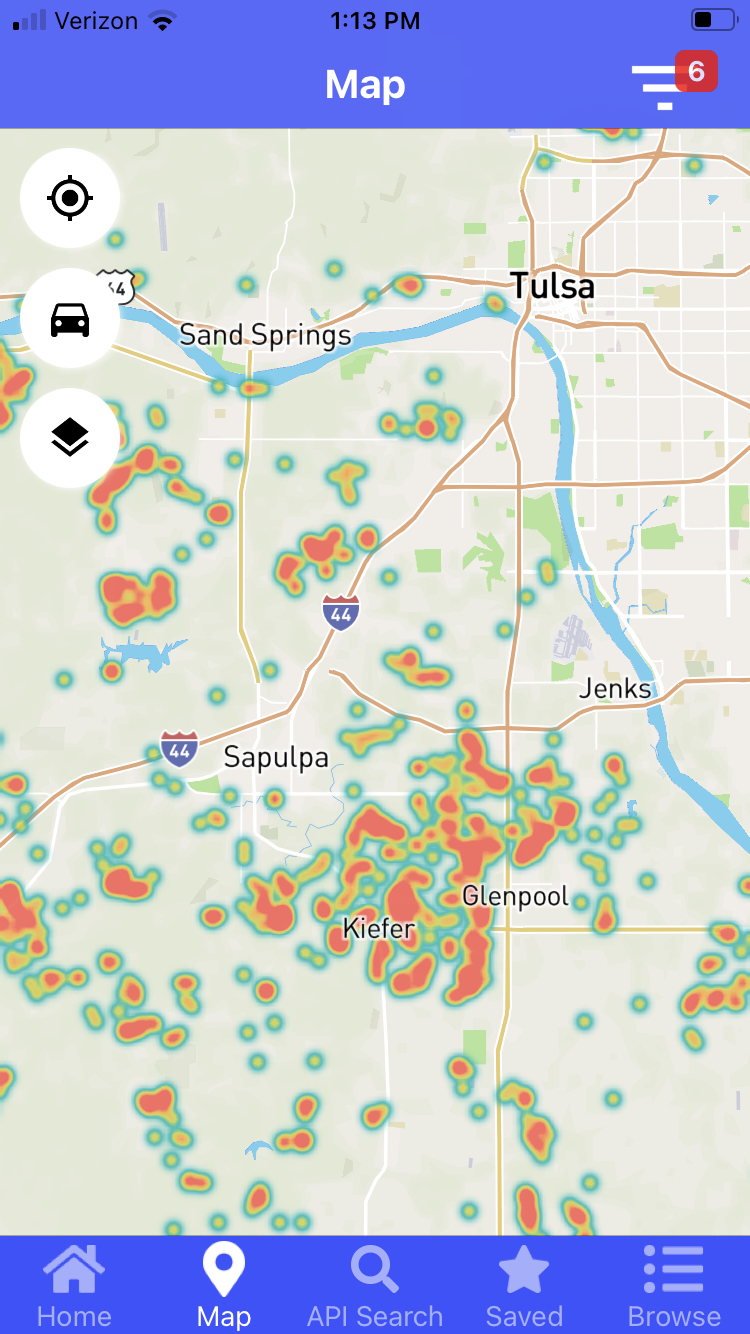

Well Finder is one of the GWPC’s products that runs on the accumulated oil and gas well data, serving up locations and information on specific wells to users via an interactive map. The app is free and publicly accessible, allowing anyone to explore a region to find out if any wells are currently operating in their area, or to search for a particular well. Users can pull up well depth, production, and location directly in the app or review the history of wells at any location. Well Finder also links to the state’s database or lets the user contact the agency directly via email for more detail. The data is updated monthly.

Fifteen states now submit data to Well Finder. Kansas, the most recent, joined in 2021. Data from Texas are currently in review to be added. The state recently changed its data-sharing policy from a subscription fee model to more open data access – a trend also manifested in the Texas Water Data Initiative, both of which are great steps toward supporting a broader Internet of Water. Additional commitments from California and New Mexico should put wells from those states on the map soon, as well. The goal is to eventually include every oil and gas well in the country, starting with GWPC member states.

Well Finder is aptly named in that it is most frequently used by agency staff, in the field, to pinpoint and inspect oil and gas wells. Many wells are located in dense fields in areas with little or no cell service, so precise coordinates, route-finding services, and offline capabilities are needed. When there are natural gas leaks, emergency responders need to know if there are other wells in the area that could pose a safety risk. Developers and city planners also use the app when expanding housing or other development in areas previously used for energy extraction.

Figure 2: Oil wells southwest of Tulsa, OK as seen in the Well Finder App

Unplugged Wells: A Growing Problem

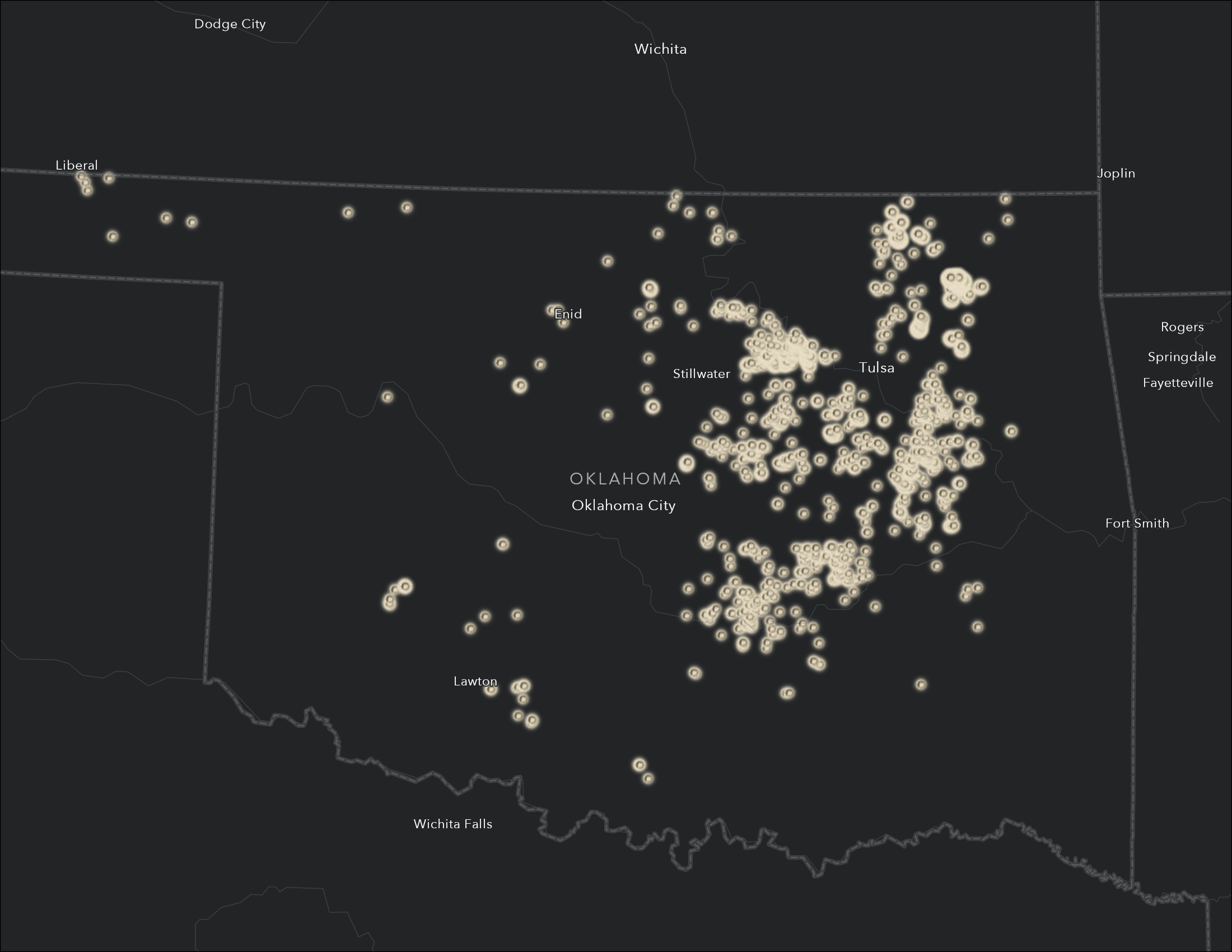

Typically, when an oil or gas well is done producing, the well is capped or ‘plugged’ to prevent any seepage of dangerous gases into the atmosphere or fluids into soil or water. However, plugging wells can be expensive, and more and more companies are abandoning wells, unplugged, because they can’t afford to pay for the entire operation. When drilling companies go bankrupt (which happened at unparalleled rates over the past two years due to declines in oil demand during the COVID-19 pandemic), the responsibility for plugging their abandoned wells falls on the states. Agency staff need to know where the wells are to safely plug them, and so unplugged wells are a growing use case for Well Finder and GWPC data more generally.

According to the EPA, there are millions of these unplugged wells scattered throughout the country. They can emit methane for decades, which contributes to climate change. They also create health risks, fire hazards, and freshwater contamination. Schools, businesses, and homes have had to be evacuated due to gas leaks traced to abandoned wells. States charge drilling companies bonds to ensure there are resources set aside for plugging wells, but often these aren’t enough and the pace of finding and plugging wells can be incredibly slow. Wyoming’s oil and gas commission, for example, plugs around 375 wells each year, with over 2,700 still to go. Pennsylvania has identified at least 200,000 abandoned wells, and these numbers are likely to grow in the near future. Companies that have recently seen prices drop, often find it easier to let their wells sit idle, in case prices go up again and they can resume pumping or sell the well to another operator. These “orphaned” wells are the iceberg waiting underneath the tip of the unplugged well dilemma. Oklahoma has a little over 800 wells on its to-plug list, but there are more than 12,000 orphaned wells in the state. The broader, accelerating transition to cleaner sources of energy may mean that these wells will never produce again, but will still need to be plugged. Federal funding to the tune of $16 Billion to help states plug all these orphaned wells recently received bipartisan support in congress.

Figure 3: Unplugged orphaned wells in Oklahoma. Source: Oklahoma Corporation Commission, Oil and Gas Conservation Division

Emerging Opportunities with Produced Water

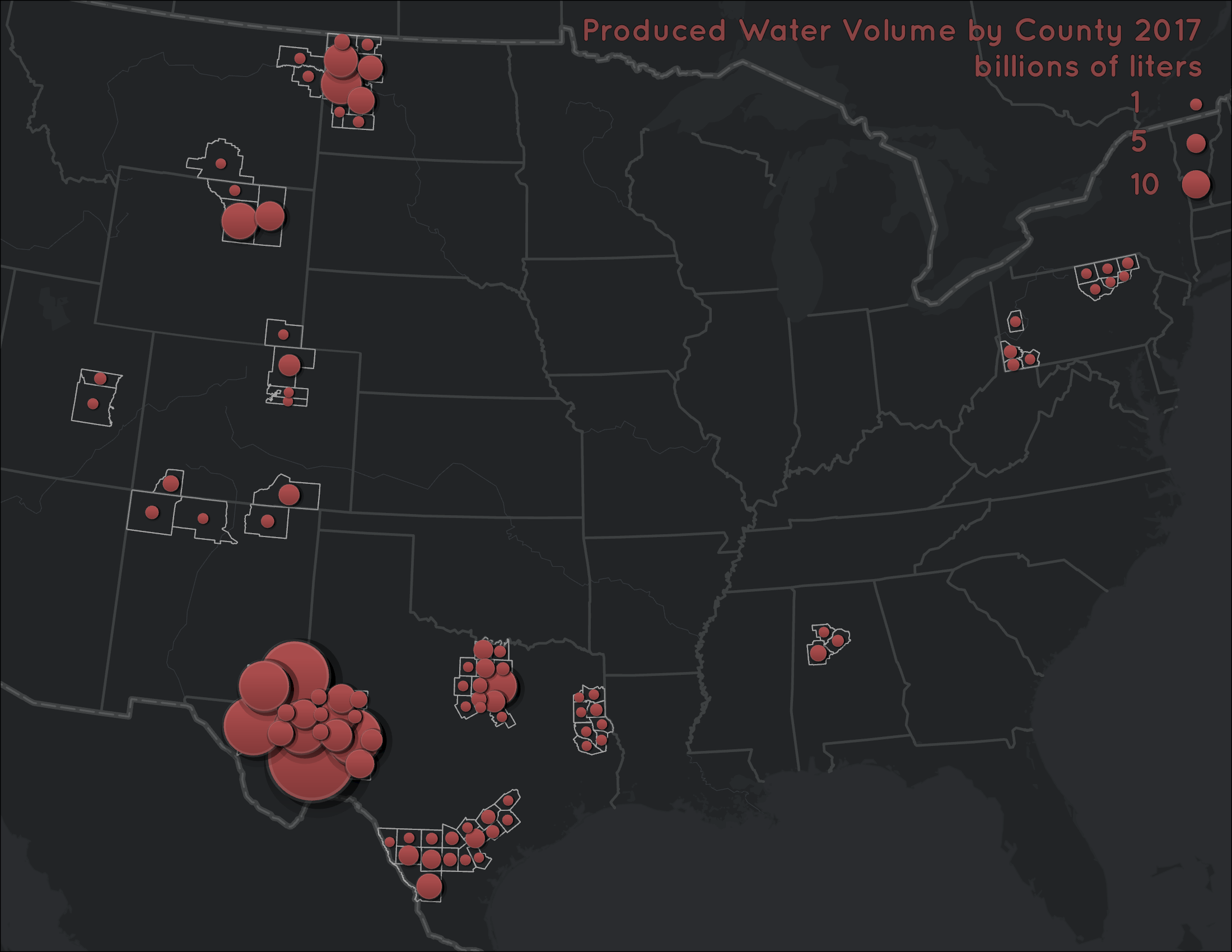

Oil and gas wells don’t just extract fossil fuels from deep in the earth, they also bring up large amounts of water. This water, called brine or produced water, is incredibly salty and can contain toxic metals or radioactive material. Recognizing produced water’s potential hazards to the environment and public health, states largely forbid its discharge to surface water or soil. Well operators typically re-inject the brine into the same geological formations that it was extracted from, keeping it isolated from underground drinking water sources and preventing contamination. The GWPC tracks all underground injection control facilities and is the expert when it comes to the technical best practices and regulation of injection.

Given the widespread, intense drought throughout the west and future potential subsurface disposal restrictions, there is growing interest in opportunities to reuse produced water and reduce the use of potable water for various applications. There is a lot of variation, however, in the quality of produced water, and large knowledge gaps on this issue persist. The clearest immediate opportunity for reuse of produced water is within the energy sector itself, as part of the hydraulic fracturing process.

Figure 4: Bridget R. Scanlon, Robert C. Reedy, Pei Xu, Mark Engle, J.P. Nicot, David Yoxtheimer, Qian Yang, Svetlana Ikonnikova. Datasets associated with investigating the potential for beneficial reuse of produced water from oil and gas extraction outside of the energy sector. Data in Brief. Volume 30. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2020.105406.

The GWPC has partnered with New Mexico to explore these opportunities and flesh out the legal and regulatory framework that would be needed to make sure any reuse of produced water is safe and wouldn’t endanger drinking water sources or harm the environment. The council recently published a study on produced water. Around the same time, New Mexico passed a law enabling some reuse of produced water in hydraulic fracturing and signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the EPA to develop regulatory frameworks for produced water reuse outside of the energy sector. Any such reuse will require intensive treatment to remove hazardous and toxic materials. The Department of Energy is funding ongoing research to develop new treatment technologies for this purpose.