Funding public data

Last Updated November 26, 2018

Rapid changes in technology require continual investments to update of data infrastructure and ensure data are preserved and available for future use. However, charging for data typically results in decreased usage and reduces the potential societal benefits of the data. We look at two examples of public agencies exploring the costs and opportunities of monetizing their data services.

Who pays for digital infrastructure?

Data can perish over time without continual maintenance. Similar to physical infrastructure (like roads and water treatment plants), digital infrastructure must be maintained and upgraded or data will no longer be accessible. Ten years ago, the go-to storage for data were DVDs. Today, many computers don’t even have a DVD drive. Those data will be lost unless time and resources are spent to transfer them to a current medium. Legacy digital infrastructure is a challenge many long-standing organizations face. Data may be stored in hard copies, scanned pdfs, floppy drives, or zip drives that may no longer be discoverable, accessible, or usable. There must be continual investment in data infrastructure to ensure data are preserved and available for future use.

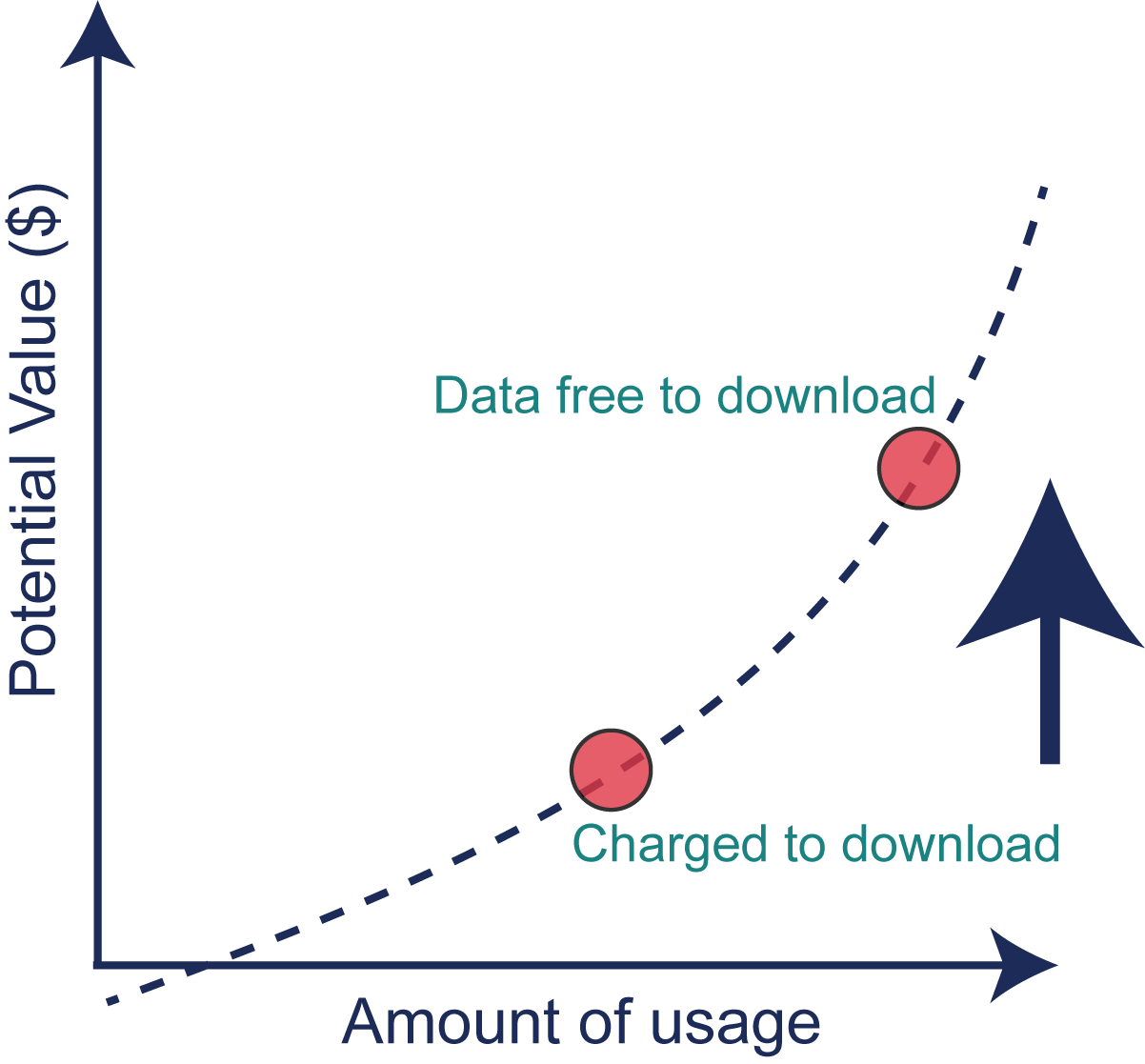

Primary data users clearly bear responsibility to cover data infrastructure upgrades. But what about data shared to secondary users? There are upfront capital cost to collect, store, and manage data. However, the marginal cost to share data is small while the potential benefits are large. Economic markets are not adept at handling products with small marginal costs. This is the case for public radio and podcasts. It costs nearly the same amount to share a podcast with 1 user as 10 users as 100 users. This is why public radio and podcasts rely on sponsorships and donations from end users. Non-rival consumption produces the classic free-rider problem where you are willing to benefit from the product as long as it is free, but you are unlikely to invest in the product if there is a cost associated with it. Many listen to, but very few financially support podcasts. Charging for podcasts or data often results in decreased usage and value. When the U.S. Geological Survey stopped charging for Landsat imagery in 2008 there was a 43% increase in new users and the average number of scenes downloaded doubled (Figure 1). Data, particularly public data, are often perceived as something that should be free, further reducing willingness-to-pay.

Figure 1: The number of downloads (potential value) of data increases when data are freely available.

While non-rival consumption is a challenge for data producers, the potential value to secondary users is enormous. This highlights the fundamental mismatch of producers bearing data costs while users accrue benefits. Who should pay for collecting, preserving, and sharing data? The non-rival nature of data undercuts the incentive for any single party to incur the costs while other parties free ride on the benefits. This creates challenges for data producers faced with making the business case to upgrade and maintain their data infrastructure for the benefit of secondary data users. But without that investment, data usage may suffer if there are insufficient financial resources dedicated to data infrastructure. Below we explore considerations for monetizing data for a state and a federal agency.

State – Monetizing the California Irrigation Management Information System (CIMIS)

CIMIS was created to disseminate statewide evapotranspiration (ET) data for irrigation management. The cost for CIMIS data collection was voluntarily shared between the state and some irrigators who purchased and maintained their own CIMIS stations because they saw immense value in these data. The voluntary cost-share of data collection helped reduce the cost to the State. California considered additional cost recovery options including privatization, user fees, or subscriptions. A sustainable revenue stream could lead to better services and increase CIMIS use over the long-term. However, the State also recognized that usage would initially decrease and the network would shrink with a cost recovery program. For instance, some private CIMIS station owners might no longer be willing to share their data and some users might not be able, or willing, to afford data access. The smaller network, decreased accessibility, and the desire to ensure access to the full record led California to continue providing free data access.

Monetizing water data is challenging given that data’s value is contingent on current conditions. Drought, higher water costs, increased public awareness, and new conservation legislation have increased the value and importance of efficient water use (and data) in California. Legislative changes can be powerful motivators to increase data usage. For instance, urban irrigation consultants credited the Water Conservation in Landscaping Act of 1990 (during a 7-year drought) for increasing CIMIS usage. The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (2014) increased the value of ET data as evident by the Open ET Project, an effort to make ET data more accessible and standardize estimates across the U.S.

Federal – Monetizing the National Weather Service (NWS)

The NWS is an impartial and authoritative voice on public safety and is a trusted partner to emergency managers by providing weather, water, and climate data. While NWS provides public data freely, their data and forecasts support a $7B private weather industry that tailors NWS products to meet the needs of particular audiences.

The NWS does not believe they should monetize their services because of their importance to public safety. However, they could benefit from private industry expertise to drive innovation, operationalize emerging technologies, and ensure forecasts adapt to meet emerging needs. Many private industries have built upon the NWS’s infrastructure and may take a more substantial role in collecting weather, water, and climate data as businesses are increasingly impacted by climate change. These data may be shared with NWS, similar to how citizen science data (CoCoRAHS) are shared with NWS, providing ‘free’ data to NWS.

The value of data can be seen through acquisitions such as the Climate Corporation by Monsanto for $0.93B in 2013 and The Weather Company by IBM for $2 billion in 2016. Monsanto saw the value of combining weather, water, and climate data with agricultural data. IBM saw potential in combining artificial intelligence, business enterprise data, and weather data. A key value proposition of companies has been to provide users with weather information in a format that is easy to interpret and relevant to their specific needs. We each have our preferred weather app or television broadcaster.

Even among private companies, approaches to monetizing weather forecasts differ. Many of the highly sought after weather apps provide personalized, hyper-local forecasts based on user location – so-called ‘personalized weather-on-demand.’ Among the top 15 weather apps in 2018, only 4 companies require payment to install the app (price ranged from $2.99 to $9.99), while the majority encourage in-app purchases for higher levels of service or to avoid advertisements. The apps that charge for data had a quarter of the number of reviews (indicator of usage) than free apps, demonstrating decreased usage of apps that require users to pay.

For more information:

-

Satellites

-

Blue Ribbon Task Force. 2010. Sustainable Economics for a Digital Planet: Ensuring Long-term Access to Digital Information.

-

GEO. 2015. The Value of Open Data Sharing.

-

Macauley. 2005. The Value of Information: A Background Paper on Measuring the Contribution of Space-Derived Earth Science Data to National Resource Management.

-

Miller et al. 2013. Users, Uses, and Value of Landsat Satellite Imagery – Results from the 2012 Survey of Users.

-

-

CIMIS

-

Cohen-Vogel et al. 1998. The California Irrigation Management Information System (CIMIS). Intended and Unanticipated Impacts of Public Investment. Choices.

-

Parker & Zilberman. 1996. The Use of Information Services: The Case of CIMIS. Agribusiness 12 (3): 209-218.

-

Parker et al. 2000. Publicly funded weather database benefits statewide users. California Agriculture 54 (3).

-

Western States Water Council. 2016. Workshop on Weather Station Networks and Irrigation Management information Systems.

-

-

NWS